December 20, 1969: Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” Reaches the Top Three on Billboard’s Music Chart

Reaching the top of the charts on December 20, 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s (CCR) song “Fortunate Son” criticized the classist nature of the American draft system. If the title of the song is unfamiliar, imagine almost any pop culture Vietnam War sequence. Chances are the iconic guitar riff is playing as a camera pans in on American soldiers sprinting through a Vietnam jungle. Appearing in films such as Forrest Gump and Tropic Thunder, the video game Battlefield: Bad Company 2: Vietnam, and the television sitcom “American Dad!,” the song “Fortunate Son” reflects the American working class’s opinion on the Vietnam War.

Reaching the top of the charts on December 20, 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s (CCR) song “Fortunate Son” criticized the classist nature of the American draft system. If the title of the song is unfamiliar, imagine almost any pop culture Vietnam War sequence. Chances are the iconic guitar riff is playing as a camera pans in on American soldiers sprinting through a Vietnam jungle. Appearing in films such as Forrest Gump and Tropic Thunder, the video game Battlefield: Bad Company 2: Vietnam, and the television sitcom “American Dad!,” the song “Fortunate Son” reflects the American working class’s opinion on the Vietnam War.

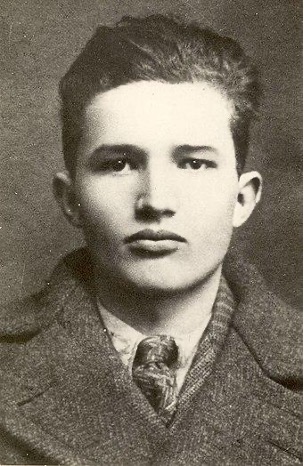

John Fogerty, the guitarist and vocalist of CCR, was inspired to write the song after learning of the December 1968 marriage of David Eisenhower (the grandson of former President Dwight D. Eisenhower) to President-elect Richard M. Nixon’s daughter, Julie Nixon. In his memoir, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, Fogerty recalled the class inequities of the draft, writing that, “you’d hear about the son of this senator or that congressman who was given a deferment from the military.”[1] David Eisenhower was one such “fortunate son.” His status as the grandson of a former president initially allowed him to avoid the draft– a privilege not afforded to those in the working class. Two years after his wedding and shortly after his graduation from Amherst College, David would enlist in the U.S. Navy. He later acknowledged “that a low number in the draft lottery…added incentive to volunteering for the Navy.”[2] While he did end up serving in the military, he avoided a position that would put him in direct combat. “Fortunate Son” channels Fogerty’s frustration with this inherent inequity.

Through Fogerty’s soulful vocals singing:

It ain’t me, it ain't me

I ain’t no senator's son, son

It ain’t me, it ain’t me

I ain’t no fortunate one, no

an anti-Vietnam War anthem arose. Fogerty himself was “no senator’s son.” In 1966, Fogerty received his draft notice and found that the only way to avoid the draft was by entering the U.S. Army Reserves along with CCR’s drummer, Doug Clifford.[3] He served as a part-time reservist until 1968.

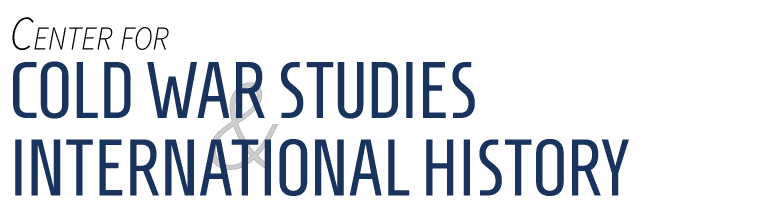

Fogerty, like David Eisenhower, managed to avoid combat service. But the lyrics of “Fortunate Son” struck a chord with working class men in combat positions precisely because they showcased the class dynamics underlying service in the Vietnam War. At the height of the conflict, surveys indicated that at least three-quarters of enlisted American men were from the working class.[4]

However, both working class men and “fortunate sons” found ways to avoid military service— earning themselves the nickname “draft dodgers.” Working class men and “fortunate sons” evaded the draft in different ways. Men with wealth and connections could afford to go to school in an effort to avoid the draft, or procure doctors’ notes to excuse them from military service in Vietnam. Future presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump were among this group, and all were later accused of draft evasion by political opponents.[5] On the other hand, the majority of working class individuals could not afford deferment from the draft. These men were, in the words of Fogerty, “born made to wave the flag” not “born silver spoon in hand.”[6] With few options available to them, these individuals were sometimes forced to flee to Canada to avoid military service. Most did not choose this option, and ended up in Vietnam. The majority of combat soldiers who served in Vietnam were working class men, and minority race soldiers.[7]

In 1968, 543,000 Americans were stationed in Vietnam, marking the height of American involvement in the war. More than 14,000 died that same year, most of them combat soldiers.[8] As death tolls continued to rise, Americans began to protest the unjust privileges of the upper class and express dissatisfaction with the classist attitudes of the draft. In October 1967, protestors declared a “stop the draft week.” From October 16 to 21, thousands of protestors marched on the Oakland, California induction center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. in an unsuccessful attempt to halt the draft. Protesters actively resisted the draft by burning draft cards, refusing induction, civil disobedience, and sometimes violence.[9] Despite the protests, an additional 6,000 men were sent to Vietnam, and the U.S. numbers in Vietnam peaked at 549,000 in 1969.

By 1973, the U.S. had withdrawn its armed forces from Vietnam, but not before 58,220 Americans and 3.1 million Vietnamese lost their lives in the conflict. An enormous death toll, the financial costs of waging the war, and the ultimate American and South Vietnamese defeat negatively affected American confidence in the federal government. Despite American efforts, Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese communist regime in 1975. Two years later, President Jimmy Carter pardoned “draft dodgers” in an effort to put an end to the divisions caused by the war.[10]

The devastation caused over many decades of failed efforts in Vietnam damaged American confidence in foreign affairs, and signaled a major Cold War defeat, which left the United States questioning its global supremacy. In some ways, the socioeconomic inequities of the Vietnam War foreshadowed the presidential scandals, conflicts in the Middle East, and increased Cold War tensions the United States would face in the decades to come. Ironically, in recent years many have misinterpreted the song “Fortunate Son” as a patriotic anthem, thanks in part to lyrics such as “some folks are born made to wave the flag, ooh, they’re red, white and blue.”[11] However, these lyrics actually signaled the unpatriotic feelings and lack of popular support for the Vietnam War. In his memoir, Fogerty noted the significance of “Fortunate Son,” proclaiming that the “[Vietnam War] wasn’t actually about the flag: it was about a very small group of rich, powerful people.” [12] With the popularity of “Fortunate Son,” Fogerty and CCR personified the broader public’s growing frustration with the ongoing Vietnam War.

Trivia:

“Fortunate Son”, was misused as a patriotic song by Donald Trump during his 2020 rally in Florida. Ironically, the song criticizes wealthy individuals (like Trump) who obtained draft deferments during the Vietnam War.

About the Author:

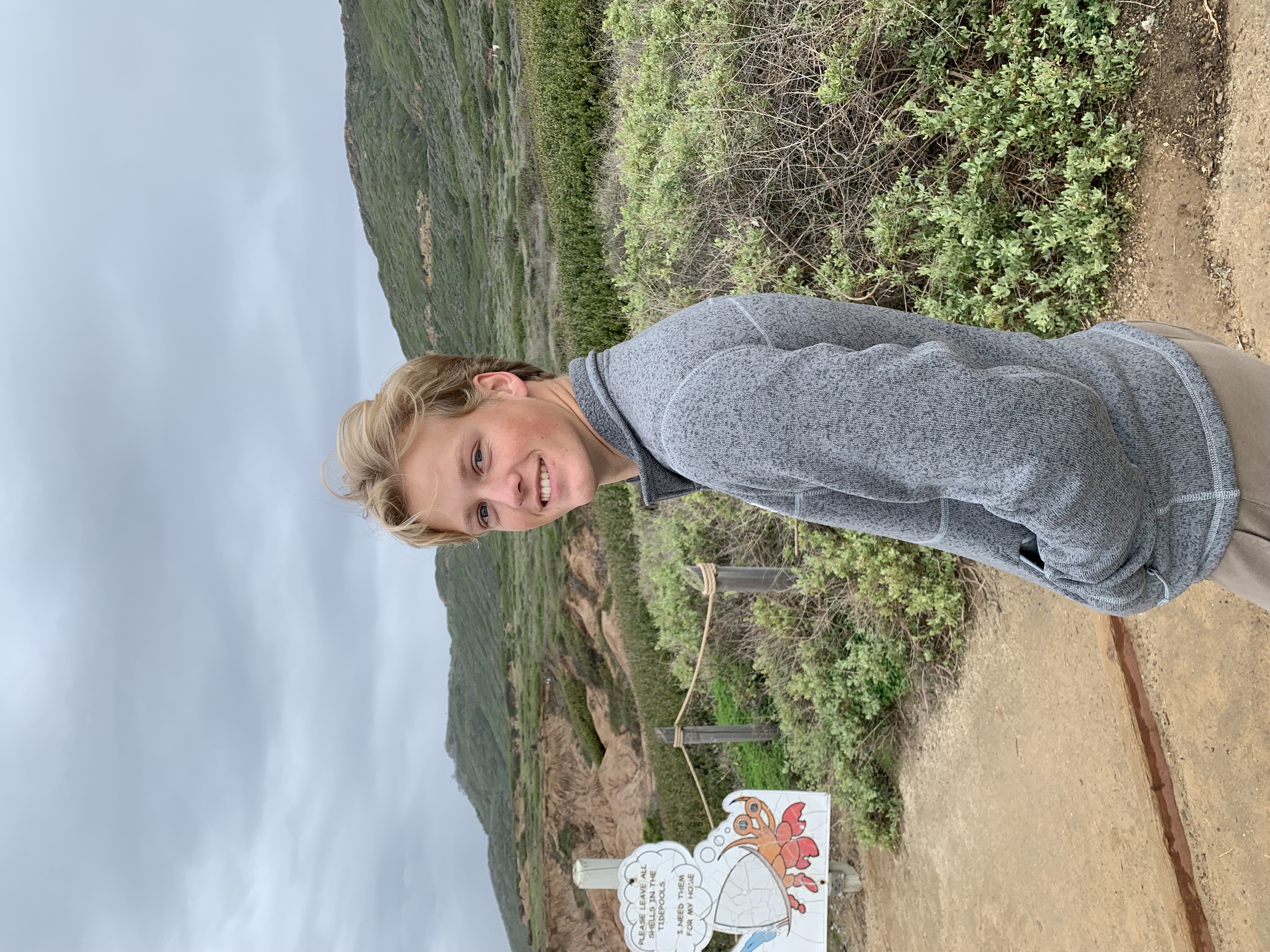

Nicole Wallius is a third-year History major at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is from Pasadena, California and is currently interested in the Vietnam War and the roles played by women, minorities, and soldiers in the conflict.

[1] John Fogerty, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2015), 264.

[2] New York Times Archives, (Newport, R.I., Oct. 25, 1970).

[3] Floris van der Laan, From “We Shall Overcome” To “Fortunate Son”: The Evolving Sound of Protest (MA, North American Studies, 2020), 54.

[4] Christian G. Appy, Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 24.

[5] History.com Editors, President Carter pardons draft dodgers, (N.p., A&E Television Networks, 2009).

[6] Creedence Clearwater, Fortunate Son, 1969.

[7] Christian G. Appy, Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam, (N.p., The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 44.

[8] James E. Westheider, The Vietnam War (Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 2007), Timeline xxi.

[9] Amanda Miller, Draft Resistance 1965-1967, Mapping American Social Movements Through the 20th Century. Retrieved Sept 19, 2022 from https://depts.washington.edu/moves/draft_resistance_map.shtml

[10] History.com Editors, President Carter pardons draft dodgers, (N.p., A&E Televisions Networks, 2009).

[11] Creedence Clearwater, Fortunate Son, 1969.

[12] John Fogerty, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2015), 152.

November 4, 1979: The Iranian Hostage Crisis Begins

On this day forty-three years ago, 52 U.S. embassy members, comprised of diplomats and citizens, were taken hostage by Iranian student militants at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran. Much of the reasoning behind the kidnapping can be explained in terms of prior U.S.-Iranian relations.

On this day forty-three years ago, 52 U.S. embassy members, comprised of diplomats and citizens, were taken hostage by Iranian student militants at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran. Much of the reasoning behind the kidnapping can be explained in terms of prior U.S.-Iranian relations.

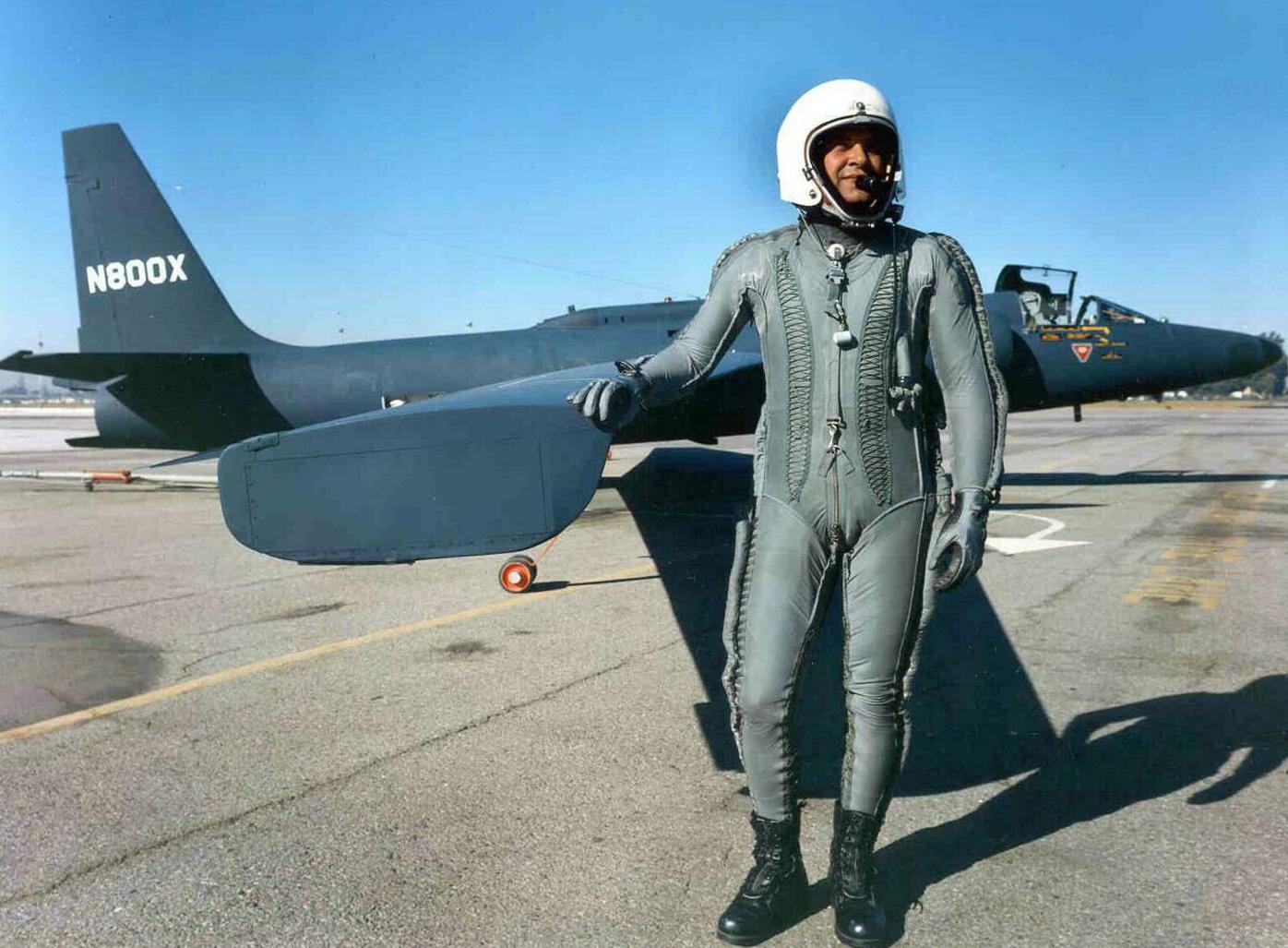

U.S.-Iranian relations soured as a result of the United States’ direct meddling in Iranian political affairs — notably the 1953 coup that violated Iran’s sovereignty as a state and overrode the will of its people. Joined by the British, American CIA officials covertly overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq for his Iranian nationalist vision of seizing a British oil company located in Iran. On August 19, 1953, Operation Ajax successfully extracted Mosaddeq from power; General Fazlollah Zahedi became the next prime minister, buttressing the monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The United States extensively funded Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s Iranian regime to dispel any sway towards communism, exporting vast quantities of the latest military technologies. The Iranian people, specifically the ayatollahs—religious leaders of the Islamic faith— viewed this tight-knight relationship with the dictator with disdain. Islamic ayatollahs under the Shia sect regarded cooperation with the Americans as traitorous and began to voice their complaints. A fierce denunciator of the Shah’s acceptance of American positions in Iranian land and oil, Ayatollah Khomeini was exiled in 1963 by the Shah. Civilian riots followed for three days, demonstrating the popularity of Khomeini and his views.

Over the fall of 1977, opposition groups, composed of secular intellectuals, ayatollah fundamentalists, and college students, grew in strength through their infiltrations into the military, many utilizing their Shiite background and religious fundamentalism to draw support. Widespread poverty and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few oil-owning elites also furthered animosity against the Shah. Social repression was fierce, and the secret police’s imprisoning of 50,000 people reinforced Iranian support behind the ayatollahs.[1]

In January 1978, Iranian students led demonstrations and protests in the city streets, culminating in year-long strife. President Carter, indeterminate in his course of action due in part to conflicting advisors, fatefully did not intervene. Shah Pahlavi, weakened by cancer and discontented with widespread hostility to his rule, abdicated his seat and fled the country in February 1979. He was succeeded by the charismatic Ayatollah Khomeini. Garnering much of his support from Iranian students, Khomeini entered Tehran in February 1979 amid celebrations to establish his government. President Carter’s decision to allow Shah Pahlavi to enter the United States in the fall of 1979 was the final straw for Iranian students. On November 4, 1979, the students attacked the U.S. embassy in Tehran, taking 52 Americans hostage. Khomeini, albeit not issuing the brazen order for seizure of the U.S. embassy, later endorsed the hostage-taking. A series of prolonged and failed negotiations followed between Carter’s administration and Khomeini’s Iranian government, with the U.S. public watching every move on their television sets.

Khomeini’s accession to power crystallized from past American interventionist efforts like Mosaddeq’s downfall. Conflating the Iranian people’s regard for Mosaddeq and Khomeini with Shah Pahlavi, the U.S. underestimated the role of popular appeal in Iranian politics. This shift in leadership would diminish America’s sphere of influence in the Middle East and jettison any hopes of a cooperative relationship with Iran.

Despite Americans knowing little about the state of Middle Eastern affairs, the Iran Hostage Crisis generated a new threat to the public about the dangers of terrorism and the growing anti-American sentiments among Islamic governments. As the historian Melanie McAlister has pointed out, many Americans blamed Islam for its blending of politics and religion; they viewed the capture of American embassy officials as an attack on America itself and its fundamental values of privacy, freedom, and secularism.[2]

Carter’s failed military rescue attempt on April 24, 1980, codenamed Operation Eagle Claw, was broadcasted on wall-to-wall media coverage: the wreckages of the downed helicopter further evoked public fury over failed American countermeasures.[3] After humiliating losses abroad in Vietnam and domestic government scandals such as Watergate, the Iranian Hostage Crisis added one more failure to the public’s mind. The hostages were eventually released on January 20, 1981, due to Iran’s heightened focus on its war with Iraq (which had broken out in September of 1980), but the political damage incurred by Carter was done. The 444 days of hostage captivity coupled with fruitless protracted bargaining with Iran helped usher in Ronald Reagan to the presidency. Both the United States and Iran felt aggrieved as the crisis subsided, and tensions remained high as the nations progressed into the 1980s.

Trivia:

If you visit Arlington Cemetery, renowned for burying the nation’s fallen soldiers, there is a monument dedicated to the Iran Hostage Crisis. The Iran Rescue Mission Memorial memorializes the 8 U.S. Armed Forces members that died carrying out the failed hostage rescue mission.

About the Author:

Nicolas Bours is a second-year chemical engineering student at the University of California Santa Barbara. A resident of the Bay Area, he has taken an interest in Cold War history, particularly through the lens of each presidential administration.

[1] Walter LaFeber, Walter, The American Age: United States Foreign Policy at Home and Abroad: 1750 to the Present. New York: Norton, 1994.

[2] Melani McAlister, “Iran, Islam, and the Terrorist Threat, 1979-1989” in Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East, 1945-2000 (Los Angeles: University of California Press), 2001.

[3] Barbara Kopple (director), Desert One, September 8, 2009.

July 14, 1958: Assassination and Overthrow of King Faisal II in Iraq

The July 14 Revolution was monumental, highlighted by the public radio denouncement of King Faisal II as a burden product of western imperialism. Heavily impacting not only United States and British foreign policy and intelligence, but also Iraq and the surrounding nations’ political stability, the overthrow of King Faisal II is considered a central event in the Middle Eastern theater of the Cold War. The assassination and overthrow of King Faisal II of Iraq marked a crucial instance during which the Middle East’s historical track shifted.

The July 14 Revolution was monumental, highlighted by the public radio denouncement of King Faisal II as a burden product of western imperialism. Heavily impacting not only United States and British foreign policy and intelligence, but also Iraq and the surrounding nations’ political stability, the overthrow of King Faisal II is considered a central event in the Middle Eastern theater of the Cold War. The assassination and overthrow of King Faisal II of Iraq marked a crucial instance during which the Middle East’s historical track shifted.

On May 19, 1916, representatives of Britain and France secretly reached an accord, known as the Sykes-Picot agreement. The treaty outlining the borders for the majority of the present Middle East was created in foresight of the eventual fall and partition of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War. Included in this secretive accord was the creation of the Kingdom of Iraq, a majority Arab state located in Mesopotamia that the British would be awarded a mandate over by the League of Nations, an international cooperation and peacekeeping organization. The Hashemites, on the other hand, were a dynastic family from Western Arabia that were early adopters of the British backed Arab Revolt, a military uprising of Arabs against the Ottoman Empire during World War I and claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad.

Through that mandate and the creation of a subordinate domestic government led by the Hashemites, the British dominated Iraq for over four decades.[1] While gaining official independence from the mandate in 1932, Iraq remained closely interconnected with the British state, partly through the monarchy. During the Second World War, for example, the British reoccupied Iraq to combat a pro-Axis coup. But through the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1948, Baghdad negotiated British withdrawal from Iraq.[2] However, the agreed upon details for withdrawal angered Arab nationalists–they ensured British control of Iraq’s foreign affairs until 1973 by creating a joint British/Iraqi military planning oversight board and ensured Iraqi dependence by tying the country’s access to military supplies and training through British institutions.

One year later, this discontent would culminate in the Al-Wathbah Uprising, where Arab nationalists took to the to the streets of urban Baghdad to display their frustrations with the British presence.[3] Arab nationalist unease in Iraq would only continue in 1955 with the Baghdad Pact, which further solidified Western interference in the Middle East.[4] Lastly, the Suez Canal Crisis pushed Arab nationalists in Baghdad to near breaking point, when Iraq, as a British ally, was forced to support the invasion of the Sinai Peninsula.[5] This decision led to widespread disapproval among the Iraqi populace, who largely connected with Gamal Abdel Nasser, the President of Egypt at the time and leader of the 1952 overthrow of the monarchy ideology.[6] These notable political grievances, when coupled with the poor economic climate, high inflation rates, and the proliferation of anti-western ideologies Iraq was experiencing following the Second World War led many in the Iraqi populace to view the Western-installed Hashemite monarchy as puppet leaders who were failing to stand up to imperialist aggression.[7]

As the Iraqi population distrusted the monarchy, other non-monarchical western backed states in the Arab world did as well. While the Suez Crisis immensely benefited Nasser's pan-Arab cause, it simultaneously undermined Arab leaders who held pro-Western policies. As Iraq was firmly in the latter camp, it increasingly became isolated from the Arab world, a fact highlighted by its exclusion from the "Treaty of Arab Solidarity" in January 1957.[8] This exclusion was only further ratified with the creation of the United Arab Republic in 1958, a pan Arab state consisting of Egypt and Syria, with the likely future addition of interested Yemen that bolstered the pan Arab movement. Iraq and Jordan, two western backed monarchies, attempted to respond to the creation of the United Arab Republic by creating their own unified state. But this state never truly crystallized largely due in part to generating little popular support.[9] This failure humiliated the Iraqi monarchy, and further romanticized pan-Arab Egypt and Syria among the Iraqi military officer corps, who at this point were increasingly turning against the Hashemite monarchy.[10]

All of these grievances crystallized at 3 o’clock on the morning of July 14, 1958, when a group of Baghdadi army officers led by General Abd al-Karim Qasim, a senior Iraqi military officer and the future inaugural Prime Minister of the new republic met at the infamous Baqubah prison north of Baghdad. Bearing rifles and pan-Arab ideologies, they marched the 20th Brigade into Baghdad and took control of the radio system, employing it to publicize the revolution. Upon picking up the microphone, Colonel Abdul Salam Arif, an associate of Qasim, “denounced imperialism and clique in office; proclaimed a new republic and the end of the old regime...announced a temporary sovereignty council of three members to assume the duties of the presidency; and promised a future election for a new president."[11]

Continuing with the coup, Arif then directed two groups from his regiment: one to al-Rahab Palace to assassinate the royal family, and the other to Nuri al-Said, the Prime Minister of Iraq and longtime ally of the Hashemite monarchy residence. While Said was initially able to disguise himself and escape, at around 8:00 AM, the King, Crown Prince, Princess Hiyam, Princess Nafeesa, Princess Abadiya, other members of the Royal Family, and several servants were machine-gunned in the Courtyard of the Royal Palace of Baghdad. Said, who had fled through the Tigris by disguising himself in a woman’s abaya, was identified and executed the next day. Fervent and hysterical, the crowds of Baghdad paraded the mutilated bodies of King Faisal II and Said for days afterwards while looting and violence ensued.[12]

The consequences of the July 14 Revolution were not only immediate and prodigious for Iraq and the Middle East, but also the United States. Qasim's unforeseen coup took Washington by shock. CIA Director Allen Dulles advised President Eisenhower that he believed it was Nasser who organized the coup. Furthermore, many in Washington, including Dulles, feared that the coup would inspire a myriad of similar revolts across the Middle East, including ones against western backed governments in Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran.[13]

The coup triggered Operation Blue Bat, the United States’ first significant military operation in the Middle East. In an attempt to provide support to the pro-western Lebanese regime and enact more control over the flow of oil from the Middle East to the West, President Eisenhower ordered an invasion of Lebanon.[14] In only 24 hours after the successful coup toppled the monarchy, thousands of marine troops stormed the beaches of Lebanon. Upon arriving at the beach, the Marines were shocked. “They expected D-Day. Instead they encountered Lebanese girls and tourists in bikinis and boys selling soft drinks and cigarettes,” reported Bruce Riedel of the Brookings Institution.[15] Jack Shulimson at the US Department of the Navy affirms this account, stating that “Further along the beach, some vacationers were enjoying the sun and others were swimming in the Mediterranean. It was a peaceful scene entirely divorced from revolutions, coup d’états, and the troubles of the cold war.”[16] Apart from this landing, which Riedel dubs “almost comical,” the operation saw the achievement of the majority of its goals in a swift manner. But this relative success, in conjunction with the lack of armed opposition US forces faced, largely misinformed US Middle Eastern foreign policy. It set a dangerous precedent for confidence in employing the use of force in the region. A precedent that would negatively impact the Middle East for decades to follow, displaying the prodigious extent of the July 14 Revolution's impact.[17]

For Iraq, the July 14 Revolution also marked a new chapter in the young nation's history. By March 1959, less than one year after the coup, Iraq withdrew from the western endorsed Baghdad Pact and created alliances with left-leaning countries and communist countries, including the Soviet Union.[18] The new government’s ties with the USSR largely allowed for the formation of an Iraqi communist party. In 1963 the Ba'ath party would gain control with a pan-Arab socialist ideology, only losing control for a few years before holding Baghdad for over three decades. As the dissenting military officers exited the Baghdad Palace, so did the reliably western backed Iraq that was present for so many years, since the inception of the country in 1921 ceased to exist.

About the Author:

Najman Mahbouba is currently a student at Los Gatos High School. Middle Eastern Politics and Policy are two of his chief research interests. He has worked on numerous social science and history related projects at Harvard, UC Santa Barbara, and San Jose State University.

[1] The Avalon Project: The Sykes-Picot Agreement: 1916, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/sykes.asp.

[2] Anglo-Iraqi Treaty (1948), Military Wiki, https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Anglo-Iraqi_Treaty_(1948).

[3] Charles Tripp, A History of Iraq, 3rd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 173.

[4] Courtney Hunt, The History of Iraq (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005), 75.

[5] Hunt, The History of Iraq, 75.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Hunt, The History of Iraq, 73.

[8] Michael N. Barnett, Dialogues in Arab Politics: Negotiations in Regional Order (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 128.

[9] Hunt, The History of Iraq, 75.

[10] Ibid.

[11]Phebe Marr, The Modern History of Iraq 2nd ed., (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2003), 156.

[12] Marr, The Modern History of Iraq, 156.

[13] Malik Mufti, “The United States and Nasserist Pan-Arabism” in David W. Lesch, ed., The Middle East and the United States: A Historical and Political Reassessment, 3rd ed. (Boulder: Westview Press, 2003), 173.

[14] Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt, “Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d”état in Baghdad,” Diplomatic History 39, no. 1 (January 2015).

[15] Bruce Riedel, “1958: When America First Went to War in the Middle East,” Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/07/02/1958-when-america-first-went-to-war-in-the-middle-east/.

[16] Jack Shulimson, Marines in Lebanon, 1958. Historical Branch, G-3 Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1966, 11.

[17] Douglas Little, American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East since 1945 (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2002), 235–37.

[18] Hunt, The History of Iraq, 76.

June 24, 1950: The Korean War begins

Although post-World War II Soviet-American tensions first flared in Europe and the Middle East, Korea was the location of the first military action during the Cold War. At the close of the Second World War, Korea had been divided at the 38th Parallel. In 1948, U.S.-backed Syngman Rhee took control of the South, while Soviet-supported Kim Il Sung established control of the North. However, both dictators sought to reunite Korea, and border conflicts were common. On June 24, 1950, North Korean forces equipped with Soviet weapons attacked South Korea across the 38th Parallel. President Harry Truman, surprised by the invasion, decided to commit American troops and UN assistance under the conviction that the fight on the Korean peninsula was the perfect opportunity to contain communism: “If we let Korea down, the Soviet[s] will keep right on going and swallowing up one [place] after another.”[1]

Although post-World War II Soviet-American tensions first flared in Europe and the Middle East, Korea was the location of the first military action during the Cold War. At the close of the Second World War, Korea had been divided at the 38th Parallel. In 1948, U.S.-backed Syngman Rhee took control of the South, while Soviet-supported Kim Il Sung established control of the North. However, both dictators sought to reunite Korea, and border conflicts were common. On June 24, 1950, North Korean forces equipped with Soviet weapons attacked South Korea across the 38th Parallel. President Harry Truman, surprised by the invasion, decided to commit American troops and UN assistance under the conviction that the fight on the Korean peninsula was the perfect opportunity to contain communism: “If we let Korea down, the Soviet[s] will keep right on going and swallowing up one [place] after another.”[1]

In the beginning, North Korean troops were largely dominant, but in September of 1950, General MacArthur oversaw the Inchon landing and pushed North Korean forces north of the 38th Parallel. After expelling the North Koreans above the parallel, U.S. forces could have declared the mission accomplished, but General MacArthur, overconfident in his military genius after his success at Inchon, continued U.S. efforts to push past the parallel and drive toward the Chinese border at the Yalu River. Unaware of Chinese troops, the American troops paused for Thanksgiving, and the next day, the Chinese attacked, ultimately pushing the MacArthur’s forces back over the 38th parallel. In July 1953, after more than two years of negotiation, both sides of the conflict signed an armistice that gave South Korea an extra 1,500 square miles of territory and created a two mile wide demilitarized zone.

The Korean War had both domestic and foreign implications. Domestically, the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 validated McCarthyism– a campaign led by Senator Joseph McCarthy that unjustly charged government officials of communist subversion. The war broke out only months after McCarthy had made his explosive allegations and heavily raised the stakes of the allegations in the midst of a hot war between the United States and Communist China.

For American foreign policy, the Korean War appeared to validate several of NSC-68’s most important conclusions. In 1950, President Truman had authorized a single, comprehensive statement—NSC-68—that advocated for the containment of communism and the build-up of the U.S. military.[2] Due in part to the outbreak of the Korean War, NSC-68 advocates did not have to work hard to win support for it. The North Korean attack confirmed NSC-68’s assumption that the Soviet Union would result in war even in the face of American nuclear superiority. Atomic weapons were inadequate to deter Soviet aggression, so as a result, U.S. defense spending rose from $13.5 billion to $48.2 billion. Furthermore, the Truman administration doubled its efforts to contain communism around the globe by laying out plans for regional defense alliances with the Middle East and Asia, increasing troops to France in Indochina, and deploying U.S. naval power to block the Taiwan Strait.[3]

About the Author:

Karen Bui (she/her/hers) is a second-year majoring in political science and minoring in history. She is from Orange County, California, but has completely fallen in love with the people, history, and natural wonders of Santa Barbara. After graduating, she hopes to apply to law school.

[1] Jeffrey Taliaferro, Balancing Risks: Great Power Intervention in the Periphery pg. 143.

[2] John Gaddis, The Origins of Containment, “NSC-68 and the Korean War.”

[3] Walter LaFeber, The American Age, pp. 502-531.

June 24, 1948: Berlin blockade begins

The Berlin Blockade started on June 24, 1948 and ended May 12, 1949, lasting for eleven months. The blockade began as an attempt by the Soviet Union to restrict the Western Allied powers (America, France and Great Britain) from entering their respective sections of West Berlin, leading to severe supply shortages for West Berlin’s citizens.[1] Initially, the blockade took shape because Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Soviet Union, was angered by the fact that the Western Allies were encouraging Germany to grow strong by rebuilding in the western zones. Stalin was concerned because a strong Germany could pose a threat to the Soviet Union. Crucially, Berlin was located within Soviet-occupied East Germany. This meant that a piece of East Germany was exposed to democratic ideals via allied-occupied West Berlin.

There were many Cold War tensions that ultimately resulted in the Berlin Blockade. One of the causes was the early 1948 announcement of the Marshall Plan. Stalin believed that the Marshall Plan would create an anti-Soviet alliance and ordered the countries under the Eastern alliance to deny assistance and aid from the United States. Due in part to the threat of Western influence in East Germany, by late June 1948 the Soviet Union blocked railroads, roads, canals, ports, and any other access paths that would allow the Western Allies to enter West Berlin from the East.[2] America responded to this blockade by airlifting over 2.3 tons of supplies— food, water, and other necessities–to the nearly 2.3 million citizens of West Berlin.

There were many consequences of the Berlin Blockade. Millions of citizens had necessities (like food, electricity, and coal) cut from their lives and suffered because of this. As the blockade went on, it was apparent that it was not going to be successful as it did not get the citizens of Berlin to reject aid from the Western powers. In addition to this, the blockade did not prevent West Berlin from growing stronger. The Berlin Blockade was broken when aircrafts from the western powers were able to get supplies and necessities to the citizens of West Berlin via the Berlin Airlift. As a result, the Berlin blockade solidified the Cold War-era division of Germany and Berlin into respective Allied and Soviet spheres. In addition to this, the Berlin blockade ultimately strengthened ties between NATO and West Germany. Perhaps most ominously, the 11-month-long Berlin Blockade was a significant moment in history that led to the construction of the Soviet construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, further solidifying the division between the East and West for the remainder of the Cold War.

About the Author:

Mattisen (Matti) Pevehouse is a 3rd Sociology major and Anthropology minor at UCSB. She is from Sacramento, California. Matti has always loved history and because of this, she has taken many history courses at UCSB, both upper and lower division. Matti is also a member of the black student union at UCSB, where she and her peers work towards social justice. She is most interested in learning about cultural and social history as it relates to sociology and social justice.

June 18, 1979: President Carter and Brezhnev sign SALT II Agreement

On this day in 1979, American President Jimmy Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT II Treaty at a summit meeting in Vienna. The treaty was the culmination of over a decade’s worth of talks first started by President Lyndon B. Johnson in an attempt to restrict the development of anti-ballistic missile systems, which threatened to disrupt the precarious balance of global nuclear power between the United States and the Soviet Union. By signing the SALT II Treaty, President Carter aimed to continue Johnson’s efforts to restrict the arms build-up, and also to continue President Richard Nixon’s detente policy with the Soviet Union. While the SALT II agreement still allowed both countries to possess a relatively large number of nuclear weapons, it was intended to prevent either country from having a clear superiority in nuclear arms, and therefore it built upon the earlier restrictions made through the first SALT treaty.

On this day in 1979, American President Jimmy Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT II Treaty at a summit meeting in Vienna. The treaty was the culmination of over a decade’s worth of talks first started by President Lyndon B. Johnson in an attempt to restrict the development of anti-ballistic missile systems, which threatened to disrupt the precarious balance of global nuclear power between the United States and the Soviet Union. By signing the SALT II Treaty, President Carter aimed to continue Johnson’s efforts to restrict the arms build-up, and also to continue President Richard Nixon’s detente policy with the Soviet Union. While the SALT II agreement still allowed both countries to possess a relatively large number of nuclear weapons, it was intended to prevent either country from having a clear superiority in nuclear arms, and therefore it built upon the earlier restrictions made through the first SALT treaty.

The predecessor to SALT II, the SALT I Treaty, was completed and signed by Nixon and Brezhnev on May, 26, 1972, and limited the number of ABM systems either side could build and the number of total defensive missiles either side could possess.[1] However, SALT I failed to address crucial issues such as limitations on the number of MIRVS each side possessed.[2] Due to this, the two nations aimed to address this issue and others by continuing the talks. It was from this second round of talks that the SALT II Treaty emerged. Guided by a provisional agreement reached by Brezhnev and President Gerald Ford in Vladivostok in 1974, SALT II limited the number of MIRVs the Soviets and the Americans each could possess to 1,320, and the total number of strategic launchers was also limited to 2,400.[3] Although the provisions of the treaty were limited in scope, it faced a great deal of domestic criticism in the United States, and Congress failed to pass the treaty immediately. This delay lasted for months, until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, after which President Carter quickly withdrew the treaty from consideration.[4]

Ultimately, despite the lack of congressional ratification, both the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to follow the terms of the treaty. This informal agreement continued until 1986, when President Ronald Reagan announced his intention to end the United States’ compliance with the terms of the treaty in response to what he viewed as Soviet noncompliance.[5] Although the SALT II Treaty was left unratified, Carter and Brezhnev’s signing of the agreement and their acceptance of its provisions represented a large step in the diplomatic efforts to end the arms build-up. While the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Reagan Administration’s general hardline anti-Soviet stance ensured that diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the United States would remain tense throughout most of the 1980s, SALT II played an important role in preventing this tension from escalating into a nuclear war.

About the Author:

Joe Shepard is a second-year history major at UC Santa Barbara. He is from Chico, California.

[1] "Strategic Arms Limitations Talks/Treaty (SALT) I and II," Office of the Historian, accessed May 31, 2022, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/salt.

[2] "Strategic Arms Limitations Talks/Treaty (SALT) I and II."

[3] Salim Yaqub, "Jimmy Carter" (lecture, History 171D, UC Santa Barbara, LSB 1001, May 10, 2022).

[4] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia, "Strategic Arms Limitation Talks," Encyclopedia Britannica, February 5, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/Strategic-Arms-Limitation-Talks.

[5] David Hoffman, "Reagan Calls SALT II Dead,” The Washington Post, June 13, 1986, accessed May 31, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/06/13/reagan-calls-....

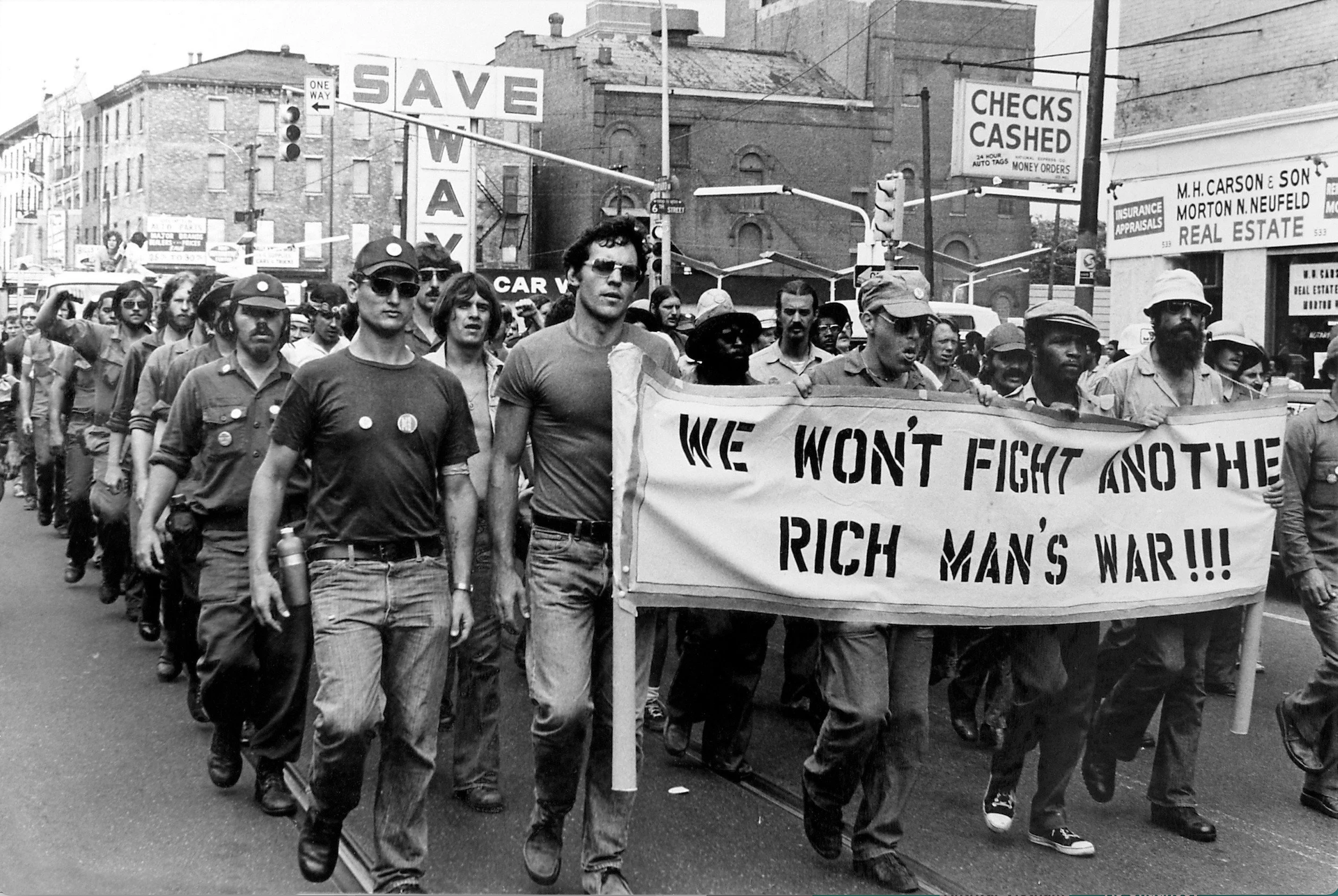

June 17, 1967: China detonates its first hydrogen bomb

Fifty-five years ago, on June 17, an H-6A fighter jet driven by pilot Xu Kejiang and his crew dropped a parachute over the Lop Nur testing site, Xinjiang. Following this drop, a flash of light suddenly erupted from the horizon of the desert, which then swiftly expanded into an enormous mushroom-shaped smoke cloud in the clear sky. Below the sky, people sang and danced vehemently on the Gorbi desert, cheering, “The first hydrogen bomb designed and manufactured by the People’s Republic of China just detonated successfully, Long Live Chairman Mao and the Chinese Communist Party!”[1]

Fifty-five years ago, on June 17, an H-6A fighter jet driven by pilot Xu Kejiang and his crew dropped a parachute over the Lop Nur testing site, Xinjiang. Following this drop, a flash of light suddenly erupted from the horizon of the desert, which then swiftly expanded into an enormous mushroom-shaped smoke cloud in the clear sky. Below the sky, people sang and danced vehemently on the Gorbi desert, cheering, “The first hydrogen bomb designed and manufactured by the People’s Republic of China just detonated successfully, Long Live Chairman Mao and the Chinese Communist Party!”[1]

To the Chinese civilians, the detonation of the first Chinese hydrogen bomb marked a new step in national technology development, which bolstered domestic unity and strengthened Mao's leadership in the late 1960s. The construction of the hydrogen bomb in the PRC was part of a long-term nuclear and space project called "Two Bomb, A Satelite" project. Some Western media also called this project the “Marshall Plan of China.” Two Bombs referred to the atomic bomb (and later the hydrogen bomb) and the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), while One Satellite referred to the artificial satellite.[2]

In October 1964, the PRC had triumphantly tested its first Atomic Bomb. Only two and half years later, the Chinese successfully exploded the hydrogren bombs as well. In response, the Chinese newspaper Ren Min Ri Bao proudly wrote that, “It only took seven years and four months for the United States to launch its first hydrogen bomb, four years for Soviet Union, and four years and eight months for Great Britain… We are the fastest people in the world...Chairman Mao’s ideology could guide us to overcome any difficulty… There is no setback in the world that could stop the Chinese people's capability to step forward.” From the CCP government’s perspective, it is the correct leadership of Chairman Mao and the proletarian people’s boundless love, worship, and loyalty to the great leader Chairman Mao that constituted a maginficently coordinated action that mobilized the manufacturing of the PRC’s first hydrogen bomb.[3]

Nevertheless, the influence of the Chinese H-Bomb detonation went far beyond its national boundaries. Internationally, the deeds of successful PRC’s H-Bomb testing also cheered up the Communist leadership in other countries, including the countries that were experiencing warfare with American allies. On the Vietnam battlefield, for example, several North Vietnam Communist party leaders Ho Chi Minh and Pham Van Dong sent congratulations to the PRC following the day of detonation.[4] Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, Chairman of the Consultative Council of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) celebrated this detonation as a significant leap forward in nuclear weapons, which not only made the PRC's national defense even stronger but also demonstrated tremendous encouragement to the Vietnamese people who were struggling against the imperialist United States.[5] Meanwhile, in the Middle East, the Arab countries were engaged in the "Six-Day War" with Israel. Mirgani Ali Mustafa, Secretary-General of the Sudan China Friendship Association, commented, "the hydrogen bomb exploded by China is a political bomb. It has inspired people all over the world and dealt a heavy blow to US imperialism and Soviet Revisionism." [6]

On the other side of the Pacific Ocean, Americans were not as hysteric as three years ago, when they first heard of the explosion of Atomic Bombs in the PRC. As the well-known American journalist, Tillman Durdin wrote, "Americans have become accustomed to the fast pace of Communist China's nuclear weapons development." His words showed that Americans were impressed but not surprised by the first detonation of the Chinese hydrogen bomb. As Durdin put forward, though PRC has indeed achieved specular success in 1967, PRC still did not own the capacity to launch its warheads through a long-range orbit. So it would not constitute immediate danger to the United States in the 1960s, but the United States should definitely keep an eye on it within the next decades.[7]

In my opinion, the hydrogen bomb detonation marked ostensible progress in PRC’s technological advancement and national defense. From the reactions of the “Third World” countries, this event served as a spiritual symbol that encouraged people from North Vietnam and Arab countries to continue their revolutionary struggles against imperialist regimes within their countries or to defend themselves against the United States Capitalism allies, which is a reflection of powers. But amid the ongoing military and ideological conflicts worldwide, the United States’ attitude toward the PRC seems elusive. On the one hand, it still perceives China as its main opponent in the world. Still, on the other hand, the United States recognized its opponent’s national power and realized that it might avoid direct military confrontations between the two countries, which paved the way for the normalization between the two countries in the 1970s.

About the Author:

Keren Zou is a third-year student at UCSB, triple majoring in History of Public Policy and Law, Asian American Studies, and Geography. Her research interests include 19th/20th century United States History, Asian American History, and Chinese Diasporas. Her projects on Asian American History have received the URCA Grant, which were presented at JHU, UCLA, and UCSB research symposiums. Keren works as a student editor at UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History and a writing tutor at Campus Learning Assistance Service. She also served as the President of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association president from 2021 to 2022. Keren hopes to pursue a Ph.D. in History after graduation. Aside from studying history, Keren is also a good chef.

[1] “Xiang Che Yun Xiao De Mao Ze Dong Si Xiang Kai Ge: Ji Wo Guo Di Yi Ke Qing Dan Bao Zha Cheng Gong 响彻云霄的毛泽东思想凯歌--记我国第一颗氢弹爆炸成功” Ren Min Ri Bao, 18 June,1967.

“ Bai Nian Shun Jian: Zhong Guo Di Yi Ke Qing Dan Bao Zha Shi Yan Cheng Gong. 百年瞬间|中国第一颗氢弹爆炸试验成功” Retrieved from Communist Website https://www.12371.cn/2021/06/17/VIDE1623900910883454.shtml 17, June, 2021.

[2] “两弹一星” Wikipedia https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%85%A9%E5%BD%88%E4%B8%80%E6%98%9F

[3] “Xiang Che Yun Xiao De Mao Ze Dong Si Xiang Kai Ge” Ren Min Ri Bao, 18 June, 1967.

[4] “Yue Nan Ling Dao Ren Zhi Dian Mao Ze Dong Zhu Xi越南领导人致电毛泽东主席” Ren Min Ri Bao, 19 June,1967.

[5] “Ruan You Shou Zhu Xi Re Lie Dian He Mao Zhu Xi Zhong Guo Bao Zha Qing Dan阮友寿主席热烈电贺毛主席中国爆炸氢弹” Ren Min Ri Bao, 21 June,1967.

[6] “Zhong Guo Qing Dan Gu Wu A La Bo Ren Min Fan Qin Lve Dou Zheng中国氢弹鼓舞阿拉伯人民反侵略斗争 Ren Min Ri Bao, 20 June,1967.

[7] TILLMAN DURDIN. "China's Bomb: Fallout Over Asia Remarkable Achievement Limited Striking Power." New York Times (1923-), Jun 25, 1967. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/chinas-bomb/docview/11747....

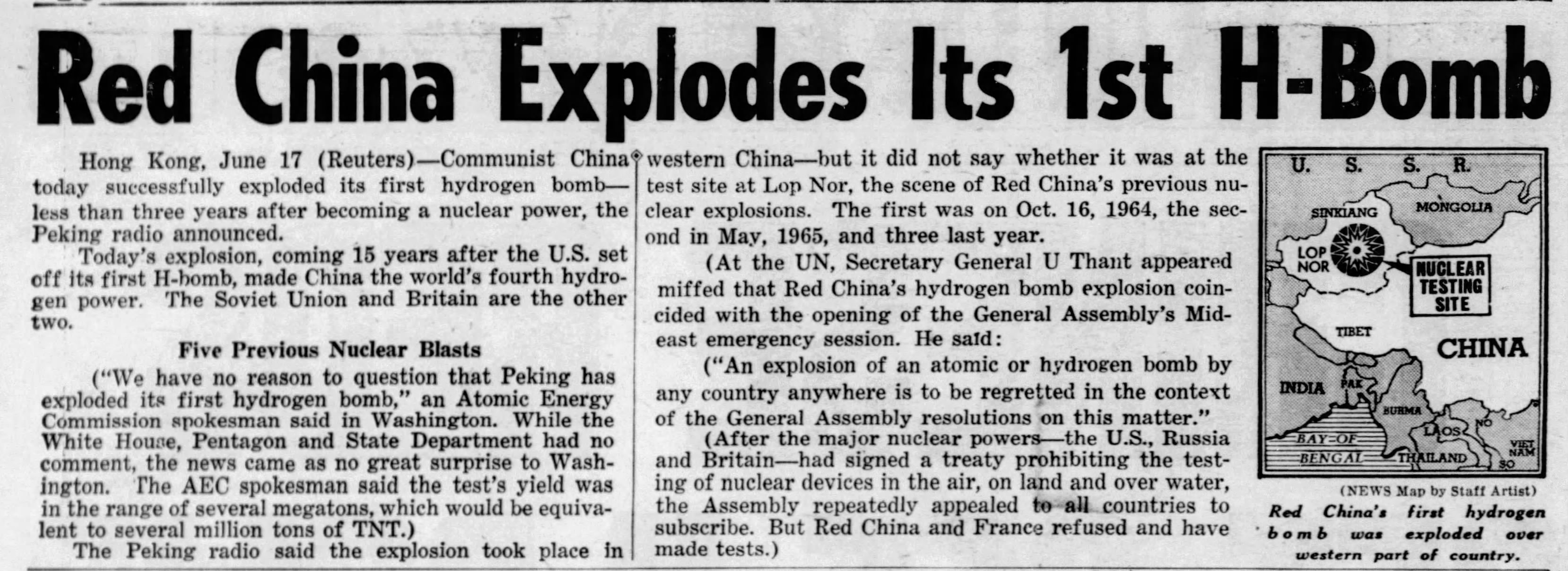

June 5, 1947: George C. Marshall announces the Marshall Plan in a speech at Harvard

On June 5th, 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall delivered a commencement speech at Harvard University. The speech was given in Harvard Yard’s Tercentenary Theatre to 15,000 people. It was the first normal Commencement since the end of the Second World War. The speech may have served to usher in a new class of Harvard graduates and close the school year, but it had long-term consequences. Marshall announced the creation of the Marshall Plan, the United States' new massive international economic aid program and foreign policy doctrine.

On June 5th, 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall delivered a commencement speech at Harvard University. The speech was given in Harvard Yard’s Tercentenary Theatre to 15,000 people. It was the first normal Commencement since the end of the Second World War. The speech may have served to usher in a new class of Harvard graduates and close the school year, but it had long-term consequences. Marshall announced the creation of the Marshall Plan, the United States' new massive international economic aid program and foreign policy doctrine.

At the conclusion of the Second World War, the United States economy was rapidly growing but there were limited global economies capable of buying U.S. goods. The Marshall Plan sought to rapidly rebuild European economies so people could buy U.S. goods. What Marshall did not say in his eleven-minute speech in Cambridge was the underlying fear motivating the Marshall Plan. The United States government feared the severe economic crisis in Western Europe from 1946 to 1947 would sway affected populations to support communism. To address this looming possibility, the United States sent $13.5 billion in aid to Europe. The U.S. aid allowed for the shipment of food, fuel, and basic necessities from the United States to Europe.

The Soviet Union's reaction to the Marshall Plan was delayed. There was a consistent silence from the Soviets until June 27th when the British and French Prime Ministers met with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov. Molotov voiced the Soviet Union's firm objections to the plan. The main concern was the United States providing mass financial assistance to Germany, a nation that had previously devastated the Soviet Union. If Germany was to receive aid, then the Soviet Union wanted complete control over the amount and distribution. Beyond Germany, Molotov wanted to know funding details for each nation receiving aid. The three nations reconvened on July 2nd for the French and British to inform Molotov his demands were not to be met. Molotov stormed out of the meeting and ended negotiations.

The plan was a success in Western Europe, both rebuilding European economies and keeping communism at bay. Its success was possible due to Western Europe's skilled labor force, strong potential for an industrial economy, and a predominantly stable political society. Latin American countries saw this aid and attempted to craft a better economic deal with the United States so they could receive increased access to the United States market. Marshall, however, refused to extend the plan to Latin America, allocating all of the resources to Europe. If the Marshall Plan was effective, then it would eventually help Latin America get access to European markets. Marshall would eventually receive a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to aid economic development in Europe. Crucially, the Marshall Plan institutionalized U.S. foreign aid programs, which are now utilized consistently across the globe. It also created long-standing close relationships between the United States and Europe. For the United States, the announcement of the Marshall Plan spurred a historic change in foreign policy from an era of isolationism to one of international engagement.

Fun Fact:

George C. Marshall was the only career military officer to have received a Nobel Peace Prize, which he was awarded in 1953.

About the Author:

Audrey Rahm is a native East Coaster who moved to Chicago and now lives in Santa Barbara (the easy winner of her favorite locations). She is a third-year Political Science major with an emphasis on International Relations. She is most interested in U.S. relations with Africa and the Middle East and will be working in South Africa this summer before graduating in the Fall.

June 4, 1961: John F. Kennedy meets with Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna

From the late 1950s into the beginning of the 1960s, tensions between the two superpowers seemed to be rising. Post-World War II Germany was split into four zones, each occupied by one of the Four Powers: the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, Berlin was also divided, but entirely located within the Soviet Union’s Eastern bloc. Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union was adamant in demanding that West Berlin (occupied by the western powers) be turned over and absorbed into communist East Germany territory. He also loudly supported revolutions as “wars of national liberation” in developing countries such as Cuba, believing that the Soviets would best be able to benefit from the resulting friendships.[1] Berlin and Cuba highlighted the agenda that President John F. Kennedy was hoping to discuss with Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961. The young president was determined to throw down a hardline and not bow down to the latter’s demands.

From the late 1950s into the beginning of the 1960s, tensions between the two superpowers seemed to be rising. Post-World War II Germany was split into four zones, each occupied by one of the Four Powers: the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, Berlin was also divided, but entirely located within the Soviet Union’s Eastern bloc. Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union was adamant in demanding that West Berlin (occupied by the western powers) be turned over and absorbed into communist East Germany territory. He also loudly supported revolutions as “wars of national liberation” in developing countries such as Cuba, believing that the Soviets would best be able to benefit from the resulting friendships.[1] Berlin and Cuba highlighted the agenda that President John F. Kennedy was hoping to discuss with Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961. The young president was determined to throw down a hardline and not bow down to the latter’s demands.

The historic meeting, however, did not subdue these tensions—if anything, it only exacerbated them. Hoping to preserve the balance of power, Kennedy sought to convince Khrushchev that it would be in both sides’ best interests to avoid rash decisions. At the same time, he aimed to demonstrate to the Soviet leader his seriousness in defending West Berlin.[2] The result was not a friendly conversation, but instead a “heated ideological debate.”[3] To make matters worse, Khrushchev saw Kennedy as extremely young and inexperienced (his own son was the same age as Kennedy), and this was made glaringly obvious by the lack of respect that Khrushchev gave Kennedy during the summit. The Soviet leader forcefully argued his ideals, while Kennedy continued in his unsuccessful attempt to sway Khrushchev in his direction. From the Western perspective, the meeting appeared to be a complete failure – no positive results came from the main issues that were discussed, and the U.S.-Soviet relationship was further strained as a result of the summit.[4]

The tensions on display at the Vienna Summit continued to play out in the remaining decades of the Cold War. In the following months, Khrushchev renewed his calls for the erasure of the Western presence from Berlin. Too many East Germans had been leaving their communist homes for the Western territory. The better educated were disproportionately represented in this statistic, creating something of a “brain drain” in East Germany. This was a major problem in the eyes of the Soviet Premier, but not one that he couldn’t solve.[5] On August 13, 1961, Khrushchev set into motion the building of the infamous Berlin Wall surrounding the Western portions of the East German capital.

Then, a year later in the fall of 1962, he moved to place intermediate range nuclear missiles in alarming proximity to the United States, thus setting the stage for the Cuban Missile Crisis.[6] Many argue that Khrushchev was motivated to take these drastic measures at least partially because he walked away from the Vienna Summit with the assumption that Kennedy was a weak leader. The Vienna Summit and its aftermath encouraged the Soviet leader to further intimidate the U.S.-led West and tip the scales in his favor.[7] In this way, the meeting between the pair on June 4, 1961 can be viewed as a major turning point in the Cold War as opposed to an outright failure.[8] It also may have been a critical deciding factor that potentially led to Khrushchev’s decision to push the two adversaries to the brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The meeting may also have influenced Kennedy’s strong stance amid the tense Missile Crisis. Regardless, the one and only meeting between the two leaders in Vienna certainly had a significant impact on the rest of the conflict, for better or worse, all the way up to the demise of the U.S.S.R. thirty years later.

Fun Fact:

At one point during the Vienna Summit, Kennedy stated that he considered Sino/Soviet forces and U.S./Western forces to be fairly equally balanced. For the rest of his life, Khrushchev would proudly boast that the President of the United States had finally acknowledged U.S.-Soviet parity.

About the Author:

Shane Scott grew up in the backyard of Joshua Tree National Park and is now a third-year transfer student at UCSB. He is majoring in anthropology with an archaeology emphasis, but is also minoring in History and has a special interest in U.S. presidents and their handling of foreign affairs. He loves to work with animals as well, and has spent time as a shelter kennel attendant and an assistant dog trainer.

[1] Walter LaFeber, The American Age: U.S. Foreign Policy at Home and Abroad Vol. 2—Since 1896, 2nd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994), 595.

[2] LaFeber, 595.; Gunter Bischof, Stefan Karner, and Barbara Stelz-Marx, The Vienna Summit and its Importance in International History (Lanhom: Lexington Books, 2013), 3.

[3] LaFeber, 595.

[4] Bischof et al., 4.

[5] LaFeber, 596.

[6] LaFeber, 597.

[7] Bischof et al., 4.

[8] Bischof et al., 4.

December 25, 1989: The Trial and Execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceauşescu

Throughout the second half of the 1980s, the dual reforms of glasnost (Russian for “openness”) and perestroika (meaning “restructuring”) sent shock waves across the Eastern Bloc. The reforms were set in place by Mikhail Gorbachev, who was dealing with economic malaise and political disillusionment in the Soviet Union. Glasnost and perestroika were largely an abandonment of the status quo and were reviled by many of the old guard communists. One such figure was President Nicolae Ceaușescu, who had ruled Romania as Secretary-General since 1965.[1] Ceaușescu had used the image and mythology of Joseph Stalin to justify his own dictatorial rule in Romania. He developed a cult of personality around himself and his wife, Elena, who served as his second-in-command in the Romanian Communist Party. Together they ruled by ferociously deploying the military and the secret police to maintain power. The two were also publicly grooming their youngest son, Nicu, to assume power after his father, which added a hereditary component to their communist dictatorship.

Throughout the second half of the 1980s, the dual reforms of glasnost (Russian for “openness”) and perestroika (meaning “restructuring”) sent shock waves across the Eastern Bloc. The reforms were set in place by Mikhail Gorbachev, who was dealing with economic malaise and political disillusionment in the Soviet Union. Glasnost and perestroika were largely an abandonment of the status quo and were reviled by many of the old guard communists. One such figure was President Nicolae Ceaușescu, who had ruled Romania as Secretary-General since 1965.[1] Ceaușescu had used the image and mythology of Joseph Stalin to justify his own dictatorial rule in Romania. He developed a cult of personality around himself and his wife, Elena, who served as his second-in-command in the Romanian Communist Party. Together they ruled by ferociously deploying the military and the secret police to maintain power. The two were also publicly grooming their youngest son, Nicu, to assume power after his father, which added a hereditary component to their communist dictatorship.

Nicolae Ceaușescu was an enigmatic figure that prided himself in being a socialist trailblazer. He would proudly tout his achievements in lengthy public addresses, reminiscent of the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. Ceaușescu wished to emulate Stalin and used his cult of personality to quench his thirst for attention. This desire for public adoration would eventually prove to be his downfall, as his December 1989 speech was interrupted by protest. In the midst of this long-winded speech, he was heckled by a large crowd of mostly young people that had assembled in the streets of Bucharest, Romania’s capital city.[2] The long-time dictator was seemingly unable to accept that his grip on power was finally waning.

The years of economic mismanagement and political repression had created a sense of desperation in the country. The mood of the crowd turned sour, and the dictator was eventually forced to flee while rioting broke out in the major urban center of Romania. The moments where Ceaușescu lost control of his people were captured on film, and came to symbolize the unraveling of communism across Eastern Europe.[3] The rioters succeeded in their goal of toppling Ceaușescu when he was forced to leave his mansion with his wife and closest advisors via helicopter. He and his posse were apprehended in Târgoviște, Romania by police who decided to hold him for trial. Throughout his capture, he denied the legitimacy of the revolution, and proclaimed himself President of Romania.

The Ceaușescus were put on trial by the National Salvation Front, which was serving as Romania’s interim government. Many of the couples’ old lieutenants made up the special jury that carried out the trial. The proceedings commenced on Christmas Day, and the two were found guilty of genocide and illegal hoarding of wealth, among other things. It is estimated the his regime was responsible for the deaths of over 60,000 people. The Ceaușescus hands were tied behind their back, and they were shot. The execution was recorded and disseminated internationally, confirming that the dictator’s reign was finally over. Ceaușescu’s fall was largely seen as a death knell for communism in Eastern Europe and demonstrated that the USSR would no longer intervene militarily to prop up its satellite regimes.

Fun Fact:

Hundreds of servicemen volunteered for the firing squad that was used to kill the Ceaușescus. Merry Christmas!

About the Author:

Ethan Moos (they/he) is a fourth year, double majoring in political science and the history of public policy and law with a minor in English. They are from Glendale, California, which makes them, in their own words, “a valley girl.” Ethan is primarily interested in studying popular culture, democracy, and political communication. They also work in the Office of the External Vice President for Statewide Affairs (EVPSA) as the Head of Staff, as well as the Office of the External Vice President for Local Affairs (EVPLA) as the County Liaison. Ethan also serves as Co-Chair Lobby Corp and Counselor to the President of UC Student Association.

[1] Tismaneanu, Vladimir. “Ceausescu Against Glasnost.” World Affairs 150, no. 3 (1987): 201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20672144.

[2] Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. “The Unbearable Lightness of Democracy: Poland and Romania after Communism.” Current History 103, no. 676 (2004): 383–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45317985.

[3] Gallagher, Tom. “Ceausescu’s Legacy.” The National Interest, no. 56 (1999): 107–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42897184.

December 8, 1987: The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty Is Signed

On this day 34 years ago, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed. When Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, came into power in 1985, he planned on creating a less hostile relationship with the United States, but President Ronald Reagan was suspicious of his intentions. When the two met in November of 1985, Reagan started to trust him a little more, especially when it came to progress on arms control. However, obstacles arose when Gorbachev demanded that the United States stop its “Star Wars” plan which focused on the development of the strategic defense initiative. Gorbachev eventually dropped this demand. Although still concerned with U.S. missile development, the Soviet Union was struggling with its own economic problems and needed to cut military spending. Also, engaging in diplomatic relations with European nations was difficult given that those countries held “no-nuke” movements.

On this day 34 years ago, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed. When Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, came into power in 1985, he planned on creating a less hostile relationship with the United States, but President Ronald Reagan was suspicious of his intentions. When the two met in November of 1985, Reagan started to trust him a little more, especially when it came to progress on arms control. However, obstacles arose when Gorbachev demanded that the United States stop its “Star Wars” plan which focused on the development of the strategic defense initiative. Gorbachev eventually dropped this demand. Although still concerned with U.S. missile development, the Soviet Union was struggling with its own economic problems and needed to cut military spending. Also, engaging in diplomatic relations with European nations was difficult given that those countries held “no-nuke” movements.

Eventually, the United States and the Soviet Union began discussions on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF).[1] In December of 1987, Gorbachev visited the United States and signed the INF treaty with President Reagan. This treaty provided the complete elimination of all US and Soviet INF missiles, totaling out to over 2,500 weapons.[2] These included “all of their nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.”[3] Such missiles fell in the range of both short and long, but could easily carry nuclear warheads. This treaty also allowed both nations to verify that there was actual destruction of such missiles through on-site inspections.[4] “The protocol explicitly banned interference with photo-reconnaissance satellites, and states-parties were forbidden from concealing their missiles to impede verification activities.”[5] They were allowed to give short notice and inspect twenty times per year to ensure no new weapons were being produced.[6] Both nations were allowed to do so for thirteen years after the treaty was signed. It is important to note that this treaty was the first of its kind. Never had there been an arms-control treaty that abolished “an entire category of weapons systems.”[7]

In 2007, the United States and Russia proposed that the United Nations General Assembly make this treaty multilateral which would place a global ban on INF missiles. However, no further action took place that would have allowed this to happen. In 2019, President Donald Trump announced that the United States was no longer going to be participating in this treaty because there was a development of the prohibited missiles in Russia. Russian President, Vladimir Putin defended his nation by stating that the U.S. anti-ballistic missile defense systems in Europe also breached the treaty because those weapons could be used for offensive purposes. Defense analysts from all around the world came to the conclusion that this treaty was outdated and with China’s nuclear repertoire growing, this Cold War agreement was no longer relevant. Presently, there has been no follow up or relevant adjustment of this treaty, which puts the world in the potential state of seeing another nuclear arms race.[8] Hopefully President Joe Biden can formulate a new plan that would prevent this from happening.

Fun Fact:

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty destroyed a total of 2,692 missiles by 1991.[9]

About the Author:

Adelaide Hobbs, a California Central Valley native, is a fourth year at UC Santa Barbara studying Political Science and History of Public Policy & Law. She is most interested in World War II and is focusing on this time in history and American Politics as she completes these two degrees.

[1] “Gorbachev Accepts Ban On Intermediate-Range Nuclear Missiles.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, November 13, 2009.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/gorbachev-accepts-ban-on-int....

[2] “Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed September 7,

2021. https://www.britannica.com/event/Intermediate-Range-Nuclear-Forces-Treaty.

[3] “Fact Sheets & Briefs.” The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at a Glance | Arms Control Association. Accessed

September 7, 2021. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/INFtreaty.

[4] “Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.”

[5] “Fact Sheets & Briefs.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.”

[9] Fact Sheet: Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.” Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, May 13, 2021. https://armscontrolcenter.org/intermediate-range-nuclear-forces-inf-treaty/.

November 2, 1963: Assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam

On this day 58 years ago, the President of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, was assassinated during the overthrow of his government by General Duong Van Minh and the South Vietnamese military.[1] President Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, made an attempt to escape capture but were later found and killed by South Vietnamese soldiers.

On this day 58 years ago, the President of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, was assassinated during the overthrow of his government by General Duong Van Minh and the South Vietnamese military.[1] President Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, made an attempt to escape capture but were later found and killed by South Vietnamese soldiers.

The death of Diem came as particularly troubling news for John F. Kennedy, President of the United States at the time. For about eight years, Diem had been working closely with the United States government in order to bring stability to the nation. Thus, when Kennedy received the news of Diem’s assassination, he jumped to his feet and rushed out of a meeting with what General Maxwell Taylor called, “a look of shock and dismay on his face which I have never seen before.”[2]

While the news was surprising, those familiar with the increasingly volatile state of affairs in South Vietnam had been anticipating it, due in part to how unpopular Diem was to the people of South Vietnam. Diem was a Catholic and the preference that he showed for fellow Roman Catholics made him unacceptable to Buddhists, who were an overwhelming majority in South Vietnam. The military tactics Diem used against North Vietnamese forces and against Buddhist protests were heavy-handed and ineffective, serving only to deepen his government’s unpopularity and isolation.[3] His 1963 brutal repression of protests led by Buddhist monks, who burned themselves alive in protest of Diem, convinced many American officials that the time had come for Diem to go.[4] When U.S. officials heard of the possibility of a coup, they stated that while they could not openly support a coup, they would accept a peaceful transition to a new government if the new leadership would be willing to negotiate with the United States. While the U.S. government always suspected that Diem was not an ideal leader, they were aware that the alternatives were far worse.

Nonetheless, the death of Diem marked a change in the United States’ approach to the Vietnam War. Three weeks after the event, President Kennedy was assassinated as well. This meant that his Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson, abruptly became the 36th President on November 22, 1963.

In the end, the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem marked the end of an eight year-long experiment to contain communism by supporting an unsavory, though non-communist, leader. The U.S government hoped that by supporting Diem, it would be possible to establish more democratic institutions in South Vietnam and assure that the country did not fall to the communism in the North. Ultimately, however, Diem would refuse to make any meaningful concessions or institute any significant new reforms, remaining unpopular and largely disconnected from the needs of the South Vietnamese people themselves.[5]

Fun Fact:

President Kennedy was presiding at a meeting when advisor Michael Forrestal handed him a telegram reporting that Diem and his brother Nhu had committed suicide after surrendering to the coup forces. Kennedy was suspicious of this initial news because he believed that devout Catholics like Diem and Nhu would not have committed suicide. It was surprising that his hunch about the situation was exactly correct. After learning that General Duong Van ("Big Minh") Minh, who had led the coup, may have ordered the assassinations, Kennedy said in a soft voice, "Pretty stupid."[6]

About the Author:

Scott Lopez is a dance teacher at the Arthur Murray of Santa Barbara. He is a fourth year finishing his History degree at UCSB. He is from Los Angeles California but has now fallen in love with Santa Barbara.

[1] “Ngo Dinh Diem Assassinated in South Vietnam.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/ngo-dinh-diem-assassinated-in-south-....

[2] Potus_geeks, Kenneth (kensmind) Wrote in. "JFK's Final Days: November 2, 1963." LiveJournal. November 02, 2013. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://potus-geeks.livejournal.com/414661.html.

[3] "Ngo Dinh Diem." Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ngo-Dinh-Diem.

[4] “Ngo Dinh Diem Assassinated in South Vietnam.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/ngo-dinh-diem-assassinated-in-south-....

[5] "United States Decides to Support Ngo Dinh Diem." History.com. November 16, 2009. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/united-states-decides-to-sup...

[6] Potus_geeks, Kenneth (kensmind) Wrote in. "JFK's Final Days: November 2, 1963." LiveJournal. November 02, 2013. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://potus-geeks.livejournal.com/414661.html

September 13, 1993: Israel and the PLO Sign the First Oslo Accord at the White House

On this day in history, 28 years ago, the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) “signed a Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, commonly referred to as the ‘Oslo Accord,’ at the White House.”[1] Also known as “Oslo I,” it was the first of two agreements (Oslo Accords) signed by both parties to create lasting peace in the Middle East.[2]

On this day in history, 28 years ago, the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) “signed a Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, commonly referred to as the ‘Oslo Accord,’ at the White House.”[1] Also known as “Oslo I,” it was the first of two agreements (Oslo Accords) signed by both parties to create lasting peace in the Middle East.[2]

The accords derive their name from the location where the secret negotiations took place, in a small villa just outside of Oslo, Norway.[3] Israel initiated the talks, in large part to uphold a campaign promise made by Prime Minister Rabin “to implement a Palestinian autonomy plan within nine months of our taking office.”[4] While Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat authorized the talks, the negotiations themselves were conducted by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Shimon Peres for Israel and Mahmoud Abbas for the PLO, who is currently the President of the State of Palestine.[5] Using the “Framework for Peace in the Middle East” document—one of the central documents of the 1978 Camp David Accords—they set out to correct its major flaw: that neither Israel nor the PLO were willing to recognize the other’s existence.[6]

On September 13, 1993, on the lawn of the White House in front of a group of impressive dignitaries invited by then-President Bill Clinton, they did just that: made formal peace with one another.[7] By signing the Declaration of Principles (Oslo I), “Israel accepted the PLO as the representative of the Palestinians, and the PLO renounced terrorism and recognized Israel’s right to exist in peace.”[8] Additionally, the peace process of Oslo I was predicated upon Israel’s withdrawal from most of Gaza and parts of the West Bank, with an elected Palestinian Authority assuming governorship over those areas. Finally, after five years, negotiators would address the most challenging hurdle to achieving lasting peace: final borders.[9]

In the end, Oslo I did more to hurt the Palestinians than help, a point made clear by Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi in his book The Hundred Years War on Palestine. He writes that if the PLO had rejected Oslo I, “the outcome would not have been worse than the loss of land, resources, and freedom of movement suffered by the Palestinians since 1993.”[10] Evidently, he is correct; since 1993, the Israeli population in the Palestine-state-to-be has grown from 250,000 to 600,000, as of 2018.[11] Then there is the Biden administration, who refused “to condemn even the clearest violation of international law and human rights by Israel” towards the Palestinians only months ago.[12]

The reality is that Palestinian President Abbas was correct when he accused Israel of ending the Oslo agreement in 2018 after then-President Donald Trump announced Washington’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, a point left undecided in Oslo I.[13] Thus, while the Oslo Accords once held the promise of extinguishing the burning hatred that exists between two groups of people seemingly forever, its memory now only endures in its capacity to add fuel to the flames.

Fun Fact:

Although Rabin and Arafat often get the credit for signing Oslo I—a fact erroneously reported by several credible sources, including the Office of The Historian, Peres and Abbas actually signed the document.[14] The ultimate authority on the subject was Bill Clinton. In his autobiography My Life, he writes: “Peres and Abbas followed me with brief speeches, then sat down to sign the agreement. Warren Christopher [the US Secretary of State] and Andrei Kozyrev [Russia’s Foreign Minister] witnessed it while Rabin, Arafat, and I stood behind and to the right.”[15] Unfortunately, at least half the sources investigated misreported this fact, which feels interesting in itself.

About the Author:

Doug Stark is a part-time everything, full-time winner who lives somewhere in California with his wife, Nataley. When he feels like it, he writes a blog about living authentically and marching to the tune of his own drummer. On this day, September 13, 2021, he graduated from the University of California, Santa Barbara, with a bachelor’s degree in English.

[1] "Milestones: 1993–2000," Office of the Historian, accessed Sept 3, 2021, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1993-2000/oslo

[2] History.com Editors. “Oslo Accords.” HISTORY, 21 Aug. 2018, www.history.com/topics/middle-east/oslo-accords.